Atmospheric Science

At Hampton University, atmospheric science research focuses on the application of advanced remote sensing technologies to study key atmospheric processes. This research aims to enhance understanding of air quality, climate variability, severe weather events, and electromagnetic wave propagation. By using remote sensing techniques, the work seeks to improve monitoring of atmospheric pollutants, support climate change mitigation efforts, and develop better weather prediction models. The integration of profiling (lidar and radar) with satellite remote sensing technologies plays a crucial role in advancing our ability to track and analyze environmental changes, contributing to the development of more sustainable and resilient solutions for addressing global challenges.

Air Pollution

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Blue Carbon

Boundary Layer Processes

Geophysical Fluid Dynamics

Lidar Remote Sensing

Planetary Science

Hampton University researchers also reach beyond the Earth’s atmosphere to our planetary neighborhood and beyond.

Planetary Thermal History

The way a planet’s internal temperature evolves is a consequence of the way heat production and heat transport processes interact over billions of years. Dr. William Moore works alongside scientists from around the world to use computer simulations of the dynamics of rocky planets to understand these interactions and what they mean for the surfaces, atmospheres, and even oceans found on the rocky bodies in the solar system and beyond.

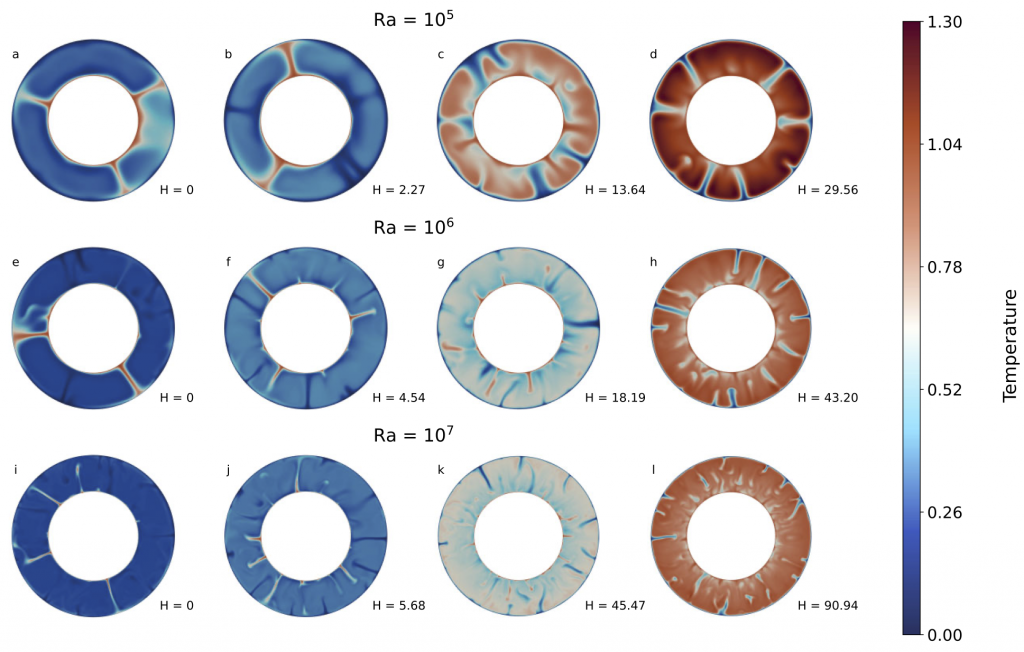

Using numerical simulations, we have identified unexpected interactions between the motion and stresses at the surface and the dynamics of the interior of rocky planets that shifts as the contribution of internal heat sources (from decaying radionuclides or tidal forces) changes over time. Rather than decaying, the surface motions increase as mantle heating decreases. This result is predicted by a simple model of interacting boundary layers [Garrido-Tomasini, et al. 2025] but was not anticipated based on standard models that treat the convective boundary layers in isolation.

Dynamics of Rocky Planets

Observations of the surfaces of all terrestrial bodies other than Earth reveal remarkable but unexplained

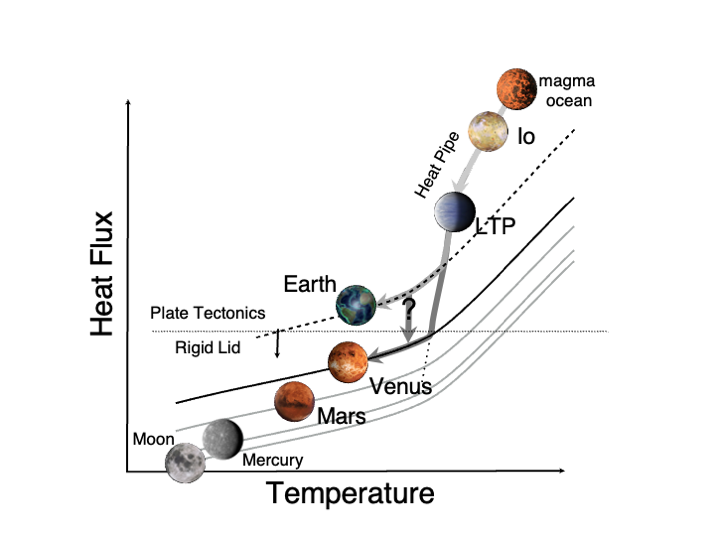

similarities: endogenic resurfacing is dominated by plains-forming volcanism with few identifiable centers, magma compositions are highly magnesian (mafic to ultra-mafic), tectonic structures are dominantly contractional, and ancient topographic and gravity anomalies are preserved to the present. In this project, Dr. Moore and colleagues have shown that cooling via volcanic heat pipes may explain these observations and provide a universal model of the way terrestrial bodies transition from a magma-ocean state into subsequent single-plate, stagnant-lid convection or plate tectonic phases. In the heat-pipe cooling mode, magma moves from a high melt-fraction asthenosphere through the lithosphere to erupt and cool at the surface via narrow channels. Despite high surface heat flow, the rapid volcanic resurfacing produces a thick, cold, and strong lithosphere which undergoes contractional strain forced by downward advection of the surface toward smaller radii. We hypothesize that heat-pipe cooling is the last significant endogenic resurfacing process experienced by most terrestrial bodies in the solar system, because subsequent stagnant-lid convection produces only weak tectonic deformation. Terrestrial exoplanets appreciably larger than Earth may remain in heat-pipe mode for much of the lifespan of a Sun-like star [Moore, et al., 2017].